With the arrival of the flash new Oxylog 3000+ there’s been quite a bit of discussion around the base recently about modes ventilation. There still seems to be quite a bit of confusion about Autoflow. In my humble opinion, mechanical ventilation is rarely particularly well taught. For most doctors, the only formal training on modes of ventilation is a hastily delivered tutorial from the flustered registrar during their first week as an ICU resident, perhaps with some random graphs scribbled on a napkin. Hardly quality clinical education. As a result ventilators continue to be scary machines for many docs. There have been plenty of opportunities in the past to own the oxylog, and I don’t want to reinvent the wheel. I think it’s worth reviewing autoflow though.

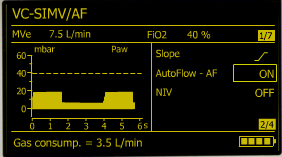

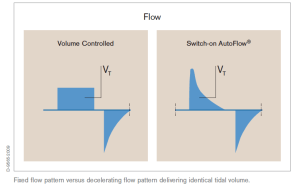

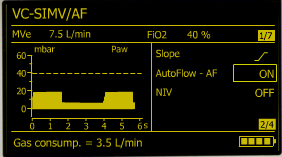

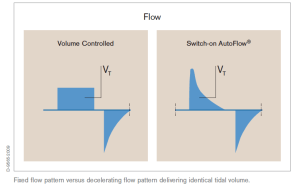

Autoflow is Drager’s method of delivering a mode of ventilation otherwise known as volume assured pressure control, or pressure regulated volume control (PRVC – Maquet’s version). Essentially its a type of ventilation that seems like volume control, in that you dial up a tidal volume, but delivers a decelerating ramp pattern inspiratory flow, so behaves like pressure control. So you get the simplicity of volume control with the benefits of pressure control.

So how does it work? Well let’s say you have a 70kg patient and you want to deliver 6mL/kg (as you always should…) so you dial up a Vt of 420mL. The ventilator will deliver a standard volume control breath of 420mL using the minimum possible flow (for a RR of 20 and an I:E ratio of 1:2 that would be 1 second Insp time and therefore a flow of 25L/min) and measure the end insp pressure. This pressure will then be used to deliver a pressure control breath as the next breath. The Vt delivered by the pressure control breath will then be compared to the set Vt, and the insp pressure adjusted up or down by 3cmH2O pre breath until the desired Vt is consistently delivered. This means that if there are dynamic changes in pulmonary compliance, the insp pressure will also change in order to deliver a constant Vt at the lowest possible Insp pressure.

Maquet’s PRVC is very similar, except that the first breath is PC, at an arbitrary Pressure, which is then adjusted over subsequent breaths to meet the set Vt. This diagram from the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s excellent Basic Assessment and Support in Intensive Care (BASIC) course sums it up pretty well

One thing to note is the Autoflow/PRVC isn’t a mode of ventilation as such. It’s just a way of delivering the breath. You still select SIMV, CMV etc as the mode of ventilation. Remember that in general you should only use CMV in curarised or very heavily sedated patients.

So why bother? Well, pressure control ventilation limits peak airway pressure and thus avoids barotrauma which may help prevent ARDS. It’s also beneficial in traumatic brain injury, as high airway pressures may be transmitted to the brain via increased venous pressure. It may also improve oxygenation in patients with poor compliance or with lung units of differing compliance. Pressure control may also be more comfortable for less heavily sedated patients.

Sounds good, what’s the catch? Well, while avoiding the main disadvantage of PCV – the inability to deliver a constant minute volume in the face of dynamic changes in pulmonary compliance – Autoflow will limit the volume delivered once the preset pressure limit is reached. In fact it will cease inspiratory flow 5cmH20 before the pressure limit is reached. The alarm “Vt low, pressure limit” will appear on the screen and the high priority alarm will sound.

I think Autoflow and it’s cousins are a good thing and together with low tidal volumes will be good for our patients, but like all new toys, we just have to have a play with them and get used to them. Don’t just take it from me though, here are some great resources that explain Autoflow and mechanical ventilation in general.

Drager Autoflow tutorial booklet

BASIC course PRVC tutorial

This third podcast provides an overview of our approach to the assessment of a critical care patient that we’re going to move from one site to another. It covers the ABCDE assessment of a ventilated patient.

This third podcast provides an overview of our approach to the assessment of a critical care patient that we’re going to move from one site to another. It covers the ABCDE assessment of a ventilated patient.