Obtaining access in shocked trauma patients can be notoriously difficult due to circulatory collapse. Those who are shocked, shut down with limited or no other options for peripheral access require central access. The cohort of patients that require this intervention in the pre-hospital setting are likely to be the most critically unwell patients we encounter.

In trauma, access to the internal jugular vein can be difficult due to cervical collars and concomitant airway interventions. Similarly pelvic binders and the potential for sub-diaphragmatic vascular injury can preclude the use of femoral access. This is why the blind subclavian approach is favoured; in experienced hands it is the most anatomically consistent approach.

The evidence for improved safety and quality with the use of ultrasound for CVC implementation is well established[i]. In fact, it’s use is so ubiquitous that the newer generation of emergency physicians are largely inexperienced in the insertion of central lines as a blind technique. This rather disconcertingly means then that the sickest patients we encounter may require a procedure that a significant number of doctors may have had very limited experience with or exposure to during their training. How can this situation be rectified or has the use of ultrasound rendered this blind subclavian “trauma line” a thing of the past?

Subclavian CVC insertion using ultrasound can be tricky due to the difficulty in visualising the vein due to the overlying clavicle. The axillary vein approach/distal subclavian can allow for ultrasound use but it represents a smaller target which may preclude it from being considered in the pre-hospital sphere where environmental factors often mean the set-up is less than ideal, not to mention the increased difficulty in a hypovolaemic shocked patient.

One proposed alternative is using the supraclavicular approach to subclavian vein cannulation. The supraclavicular approach is not a new technique, but it is underutilised. In fact, it was first described by Yofa in 1965 as an alternative to the infraclavicular approach for SCV cannulation[ii]. This approach is a bit of a misnomer as in reality it involves cannulation of the brachiocephalic vein (BCV) origin. The right BCV origin is preferred as it is more superficial, larger and straighter. Its use is perhaps most widely studied in the paediatric population, where this approach is found to have a high success rate and a low procedural complication rate[iii],[iv].

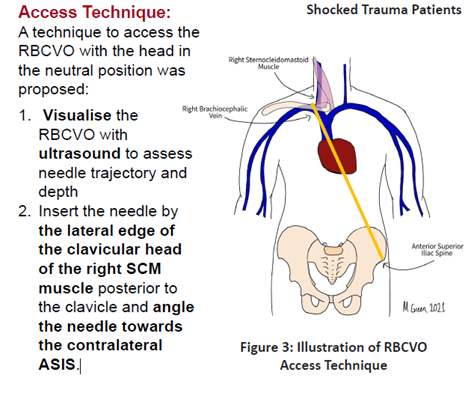

Preliminary studies including a biometric analysis of CT scans and prospective ultrasound study suggest that right BCV origin access is feasible in shocked trauma patients and the RBCV does not collapse in severe shock[v]. The right BCV is preferred as it is more superficial and straight compared to the left BCV which was observed to be deeper and has a more tortuous course[vi]. One approach to obtaining BCV origin access (fig.1) suggests using ultrasound to determine needle trajectory and depth and then proceeding without ultrasound guidance. This would therefore remove some of the limitations (perceived or real) around time delays associated with using ultrasound for central access as there would be no need for probe covers and positioning of the portable ultrasound (which often needs the help of a second operator, a significant limitation in a small prehospital medical team).

A small single centre study conducted in an Australian tertiary trauma centre on shocked trauma patients presenting to ED showed that right BCV access is feasible and had a higher success rate for 1st attempt access than the subclavian vein (63 vs 48%)[iv]. Some limitations were noted however in visualisation of the vein with ultrasound in obese patients and those with subcutaneous emphysema.

Perhaps more importantly this technique may serve to bridge the gap between the newer generation of critical care physicians who may be more reluctant to adopt a completely landmark base/blind approach to central access. At the very least, knowledge of it as an option in the armamentarium of retrieval and critical care providers is important. It is currently the subject of future research and publication in the emergency department setting. Its use in the prehospital environment is not well known or studied and may be an interesting area for future research.

[i] Leibowitz A, Oren-Grinberg A, Matyal R. Ultrasound Guidance for Central Venous Access: Current Evidence and Clinical Recommendations. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2020;35(3):303-321. doi:10.1177/0885066619868164

[ii] Yofa D. Supraclavicular subclavian venepuncture and catheterisation. The Lancet. 1965;286:614–7

[iii] Breschan C, Platzer M, Jost R et al. Consecutive, prospective case series of a new method for ultrasound-guided supraclavicular approach to the brachiocephalic vein in children. Br. J. Anaesth. 2011; 106: 732–737.

[iv] Breschan C, Graf G, Jost R et al. A retrospective analysis of the clinical effectiveness of supraclavicular, ultrasound-guided brachiocephalic vein cannulations in preterm infants. Anesthesiology 2018; 128: 38–43.

[v] M. Green et al. Right Brachiocephalic Vein Origin Access for the Resuscitation of Shocked Adult Trauma Patients. Poster presented at Australia, New Zealand Trauma Society Conference, Melbourne, VIC, Australia. October 2023.

[vi] Xia R, Sun X, Bai X et al. Efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided cannulation via the right brachiocephalic vein in adult patients. Medicine 2018; 97: e13661.